Hello, and welcome back to a new post!

In this article, we are going to write a simple linux container from scratch, in less than 100 lines of code.

I’m going to be using c/c++, and explaing each step along the way.

What’s a container?

If you are not familiar with containers, basically it’s just a set of processes isolated from the other processes. It behaves as if it is in its own world.

Use case

Imagine you created a wonderful open source application, and it got attention from other users. In order for the application to run, it needs many specific packages, libraries and configurations that may not be compatible with each user’s environment.

Your application is working perfectly on your own machine, but when other users try to use it, they get version conflicts and many other issues related to compatibility between libraries etc…

How would you solve the issue? you made a great effort creating the application and making it available for others, but it’s to no avail if no one can actually run it…

The easiest solution is containers. You would package your application into a container, that it has every piece of software necessary to run the application.

Now users would simply build and run the container, and have the application working, without altering any of their existing configurations/libraries.

Setting up the environment

Start by creating a new folder that will hold our project. I’m naming it container101.

Inside the container, create a new file container.cpp

Write a simple hello world to make sure everything is good.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

#include <iostream>

int main(void)

{

printf("containers 101\n");

return (0);

}

Compile and run the program

1

g++ container.cpp -o container -Wall -Wextra -Werror && ./container

Process ?

Earlier we discussed that a container is nothing but processes, but what is a process?

In a basic level, a process is just a running program, that’s it.

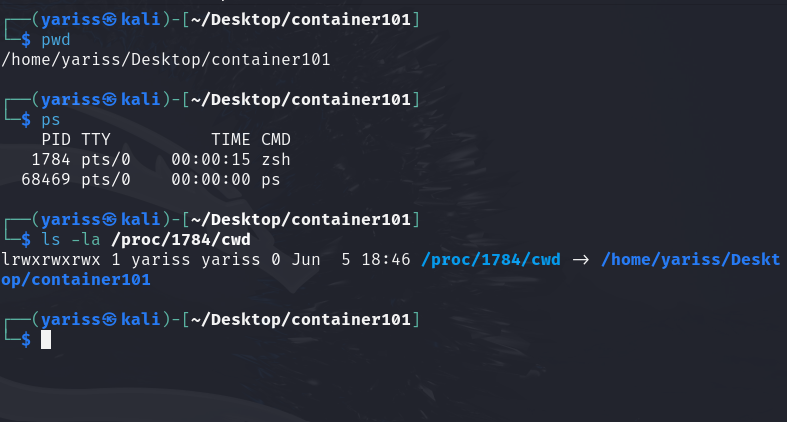

In linux, everything is a file, and when we are talking about processes, we can inspect them via the /proc which is a special file system mounted at boot time.

Example

- pwd : print working directory

- ps : allows you to view informations about running processes, in this case we are interested in

zshprocess which is our currentshell /proc/1784/cwd:- /proc is the proc file system, which has information about all system processes.

- 1784 is our shell process

- cwd is a special file, a symbolic link to our current working directory

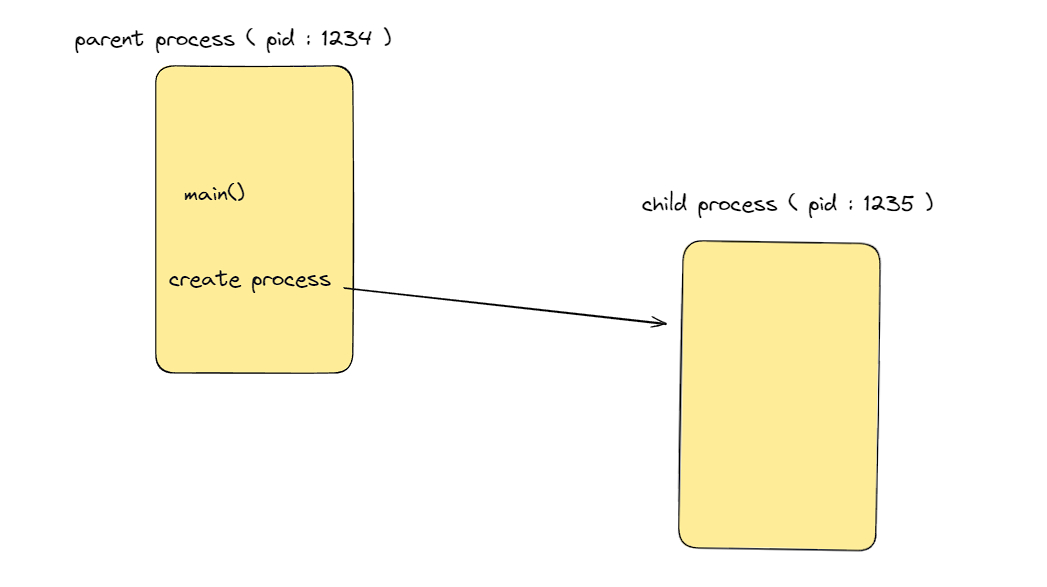

Picture processes as a tree, each node represents a process, and it may or may not have a child.

The root node is init, with the pid of 1.

Coding

To achieve this behaviour, there is a system call, called clone().

clone() takes 4 parameters:

- the function that’s going to run

- a custom stack

- some flags

- parameters for the function that’s going to run.

For now, let’s create a simple function that prints something

The Child function

1

2

3

4

5

int fn(void *args)

{

printf("from child\n");

return (0);

}

The function signature needs to be as provided above.

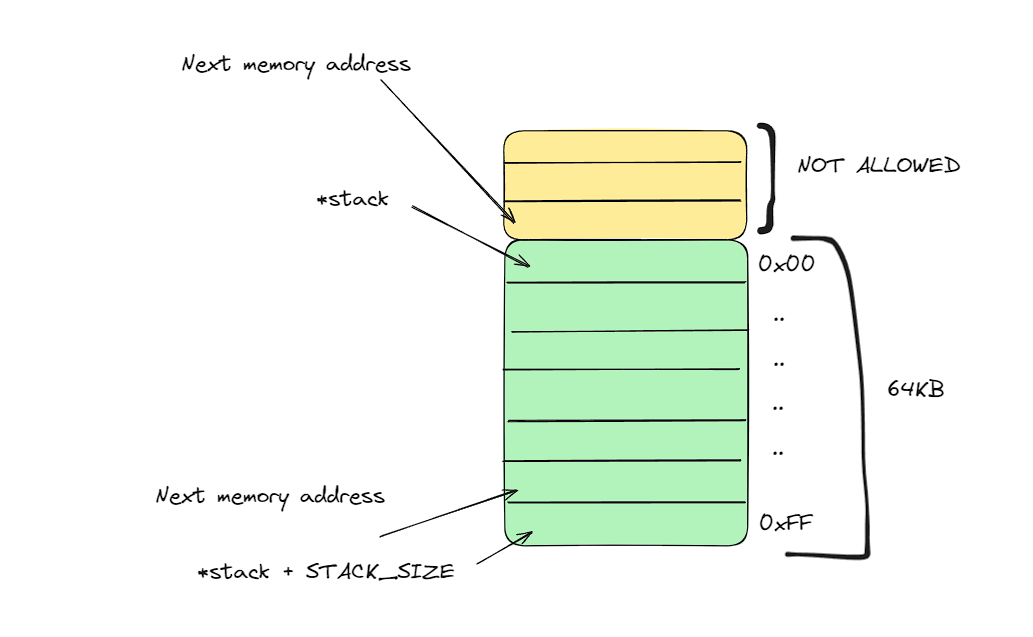

Next, we need a stack.

Basically a stack is just a char array of X bytes. We are going to set the size as 64 KB

The stack

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

#define STACK_SIZE (1024*64)

char *create_stack(void)

{

char *stack;

stack = new(std::nothrow) char[STACK_SIZE];

if(stack == nullptr)

{

std::cerr << "Error allocating memory\n";

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

return stack + STACK_SIZE;

}

This function allocates a memory buffer of size 64KB, and returns the address of the first element of the stack.

We return stack + STACK_SIZE because the stack grows in the opposite direction, here is an illustration that explains it:

If we returned stack, the next memory address is above us, which is out of bounds.

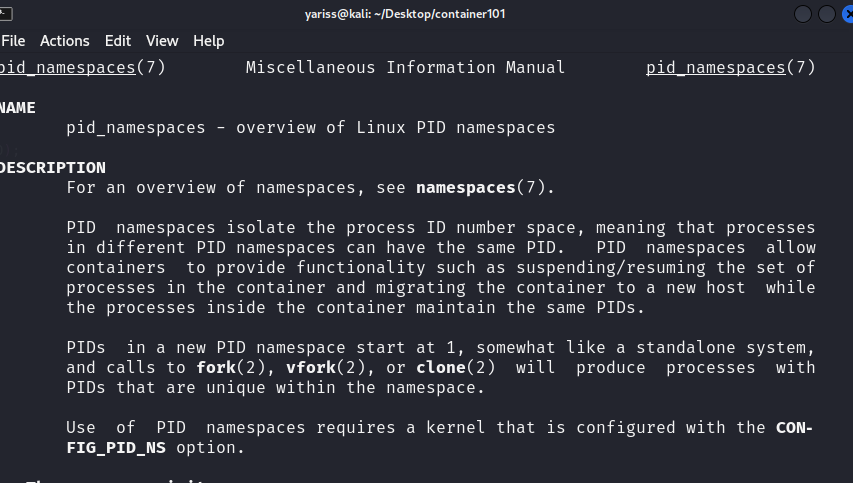

The flags - Namespaces

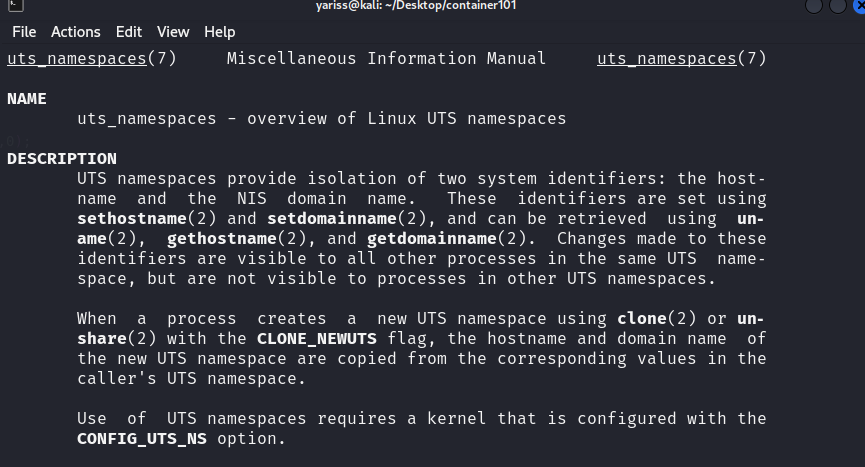

Before we talk about flags, let’s first talk about namespaces.

Namespaces are the magic behind containers, they allow a layer of isolation between processes.

There are multiple types of namespaces, but in this article, we are going to talk about 2 of them: UTS namespace and PID namespace.

UTS Namespace

In short, it allows us to have different hostnames and

PID Namespace

This will create the illusion of containerization, meaning when we will create a new process, the process parent is going to have an id of 1.

Finally, we will need a special flag called SIGCHLD, which is necessary and tells the process to emit a signal when finished.

Define the flags as the following:

1

#define FLAGS (SIGCHLD | CLONE_NEWUTS | CLONE_NEWPID)

Now we need to put all of this together

Let’s create a main function and call clone()

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

#include <iostream>

#include <sys/wait.h> // for SIGCHLD

#define STACK_SIZE (1024*64)

#define FLAGS (SIGCHLD | CLONE_NEWUTS | CLONE_NEWPID)

char *create_stack(void)

{

char *stack;

stack = new(std::nothrow) char[STACK_SIZE];

if(stack == nullptr)

{

std::cerr << "Error allocating memory\n";

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

return stack + STACK_SIZE;

}

int fn(void *args)

{

printf("from child\n");

return (0);

}

int main(void)

{

printf("containers 101\n");

clone(fn, create_stack(), FLAGS, 0);

return (0);

}

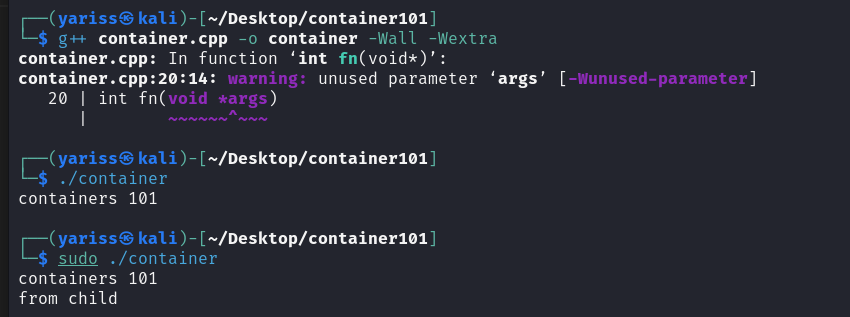

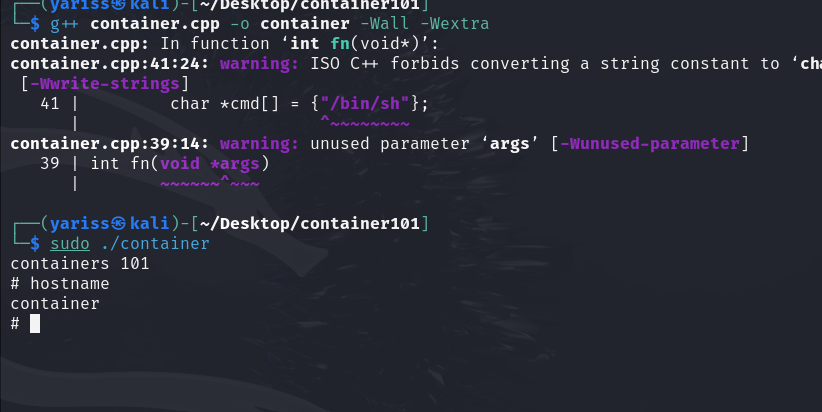

Compile the program

1

2

g++ container.cpp -o container -Wall -Wextra

# ignore warnings

Run the program (needs sudo privileges)

1

sudo ./container

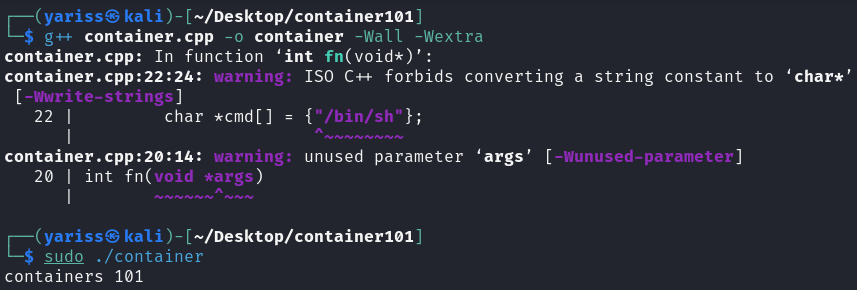

As you can see, it’s working, but a simple print won’t do the job, we need to execute a shell.

Let’s modify our function, so that it executes /bin/sh.

1

2

3

4

5

6

int fn(void *args)

{

char *cmd[] = {"/bin/sh", NULL};

execvp(cmd[0],cmd);

return (0);

}

Nothing happens, why?

In order to understand, add this printf after clone.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

int main(void)

{

printf("containers 101\n");

clone(fn, create_stack(), FLAGS, 0);

printf("parent finished execution\n");

return (0);

}

What’s happening is that the parent finishes execution, without waiting for its child.

To fix the proble, we can add wait(0), to wait for any available children.

Replace the print statement with wait(0), recompile and execute, you will spawn a sh shell !

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

int main(void)

{

printf("containers 101\n");

clone(fn, create_stack(), FLAGS, 0);

wait(0);

return (0);

}

We were successfully able to execute a shell, but we still have a lot of work to do.

Let’s define the next steps of our project:

- Change the hostname

- Clear the environment variables

- Set new env variables

- TERM

- PS1

- PATH

- Change the root file system

- Change directory into this root file system

Let’s create a function for each step.

Hostname

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

void f_sethostname(const char *hostname)

{

struct utsname uts;

if(sethostname(hostname, strlen(hostname)) == -1)

{

std::cerr << "Error setting hostname\n";

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

if(uname(&uts) == -1)

{

std::cerr << "Error setting hostname\n";

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

}

Let’s call it before we execute a new shell.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

int fn(void *args)

{

char *cmd[] = {"/bin/sh"};

f_sethostname("container"); // here

execvp(cmd[0],cmd);

return (0);

}

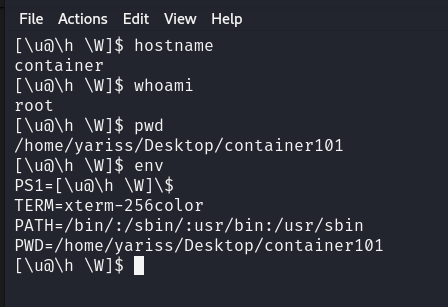

Env variables

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

void f_setenv(void)

{

clearenv();

setenv("TERM", "xterm-256color", 0);

setenv("PS1","[\\u@\\h \\W]\\$ ",0);

setenv("PATH", "/bin/:/sbin/:/usr/bin:/usr/sbin", 0);

}

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

int fn(void *args)

{

char *cmd[] = {"/bin/sh", NULL};

f_sethostname("container");

f_setenv(); //here

execvp(cmd[0],cmd);

return (0);

}

This runs fine, but there is a slight problem with it, PS1 is not interpreted.

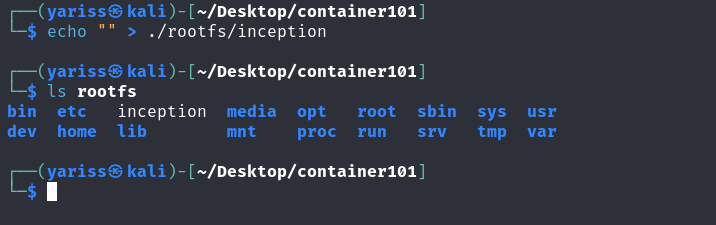

ROOT FS

Let’s download a very tiny file system, alpine.

Here is the link: https://dl-cdn.alpinelinux.org/alpine/latest-stable/releases/x86_64/alpine-minirootfs-3.20.0-x86_64.tar.gz

1

curl -Ol https://dl-cdn.alpinelinux.org/alpine/latest-stable/releases/x86_64/alpine-minirootfs-3.20.0-x86_64.tar.gz

1

2

mkdir rootfs

tar -xzf alpine-minirootfs-3.20.0-x86_64.tar.gz -C rootfs

Now we create a function that changes the root file system from the current directory to rootfs.

1

2

3

4

5

void f_set_fs(const char *folder)

{

chroot(folder);

chdir("/");

}

Call the function

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

int fn(void *args)

{

char *stack;

char *cmd[] = {"/bin/sh", NULL};

stack = create_stack();

f_sethostname("container");

f_setenv();

f_set_fs("rootfs"); //here

execvp(cmd[0], cmd);

return (EXIT_SUCCESS);

}

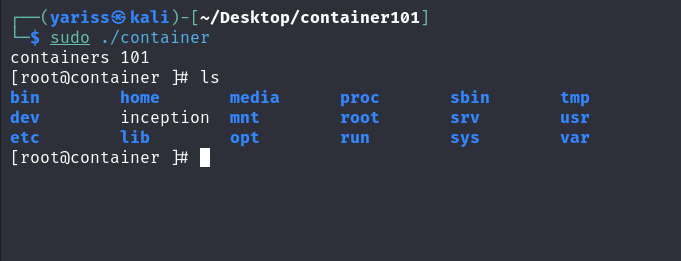

Compile & run

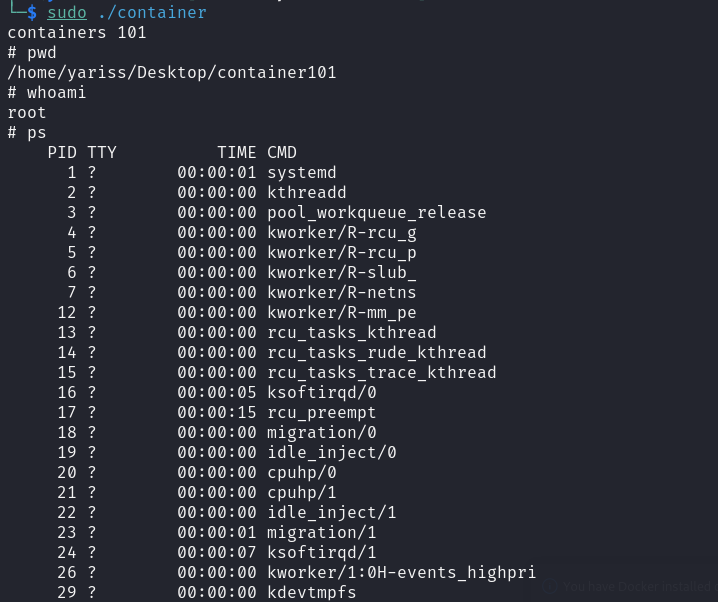

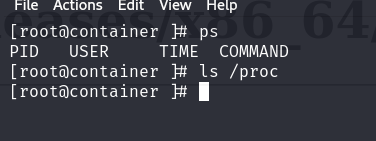

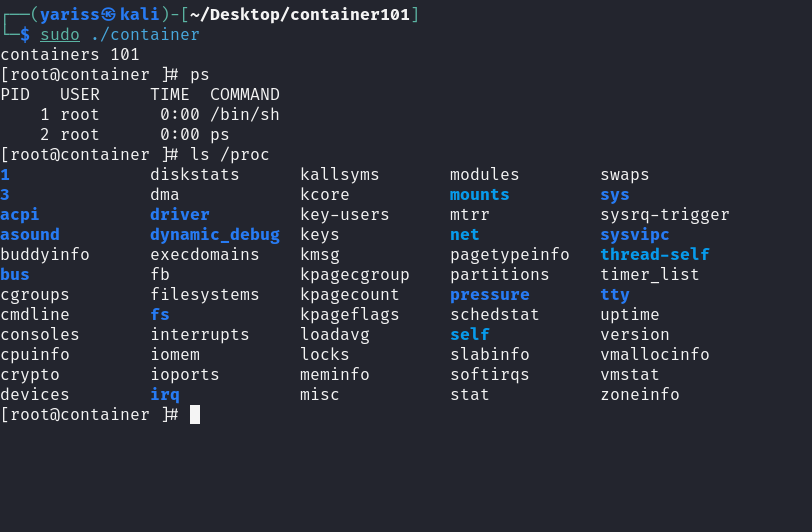

Damn, that looks like a container!! But we haven’t finished yet, if we type ps, no process is shown.

This is because we changed the root file system to rootfs, which has /proc empty.

In order to show current running processes, we need to mount the process file system to /proc.

Add this line of code before execvp

1

mount("proc","/proc","proc",0,0);

Compiling and running the program again, we get this:

Nice, it’s working as expected.

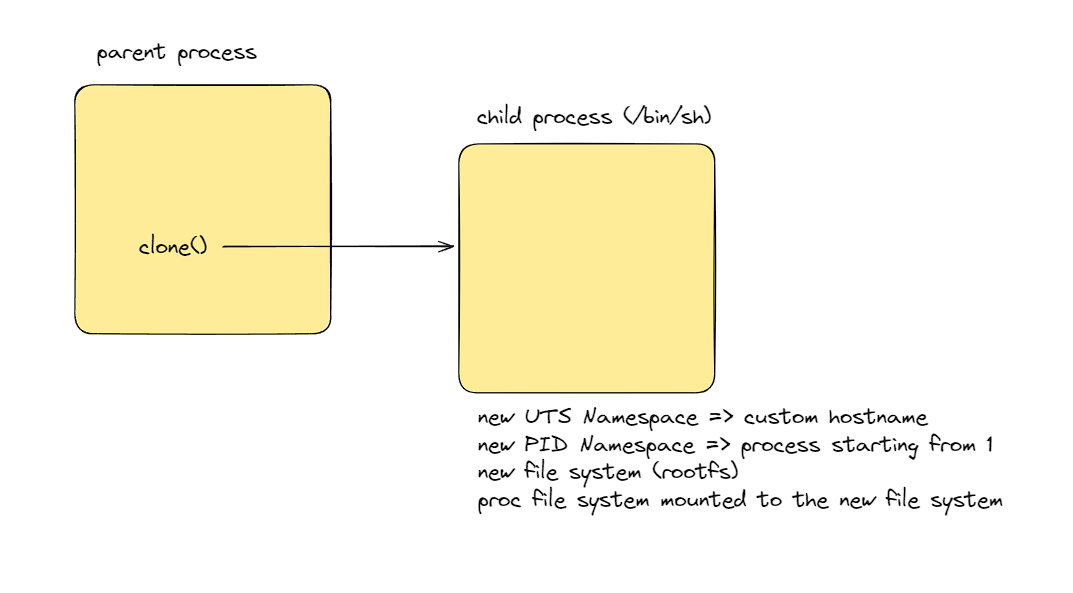

Wrapping Up

Here is a final illustration that sums up what we have done so far

And here is the entire code

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

#include <iostream>

#include <sys/wait.h>

#include <cstring>

#include <sys/utsname.h>

#include <sys/mount.h>

#define STACK_SIZE (1024*64)

#define FLAGS (SIGCHLD | CLONE_NEWUTS | CLONE_NEWPID)

void f_sethostname(const char *hostname)

{

struct utsname uts;

if(sethostname(hostname, strlen(hostname)) == -1)

{

std::cerr << "Error setting hostname\n";

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

if(uname(&uts) == -1)

{

std::cerr << "Error setting hostname\n";

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

}

void f_set_fs(const char *folder)

{

chroot(folder);

chdir("/");

}

void f_setenv(void)

{

clearenv();

setenv("TERM","xterm-256color",0);

setenv("PS1","[\\u@\\h \\W]\\$ ",0);

setenv("PATH", "/bin/:/sbin/:usr/bin:/usr/sbin", 0);

}

char *create_stack(void)

{

char *stack;

stack = new(std::nothrow) char[STACK_SIZE];

if(stack == nullptr)

{

std::cerr << "Error allocating memory\n";

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

return stack + STACK_SIZE;

}

int fn(void *args)

{

char *stack;

char *cmd[] = {"/bin/sh", NULL};

stack = create_stack();

f_sethostname("container");

f_setenv();

f_set_fs("rootfs");

mount("proc","/proc","proc",0,0);

execvp(cmd[0], cmd);

return (EXIT_SUCCESS);

}

int main(void)

{

pid_t pid;

printf("containers 101\n");

pid = clone(fn, create_stack(), FLAGS, 0);

if (waitpid(pid, NULL, 0) == -1)

{

std::cerr << "Error cloning...\n";

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

return (0);

}

Further improvements:

- Implement security aspects utilizing

cgroups- Limit process creation

- Limit resources

- …

- Better error handling

- Dynamic configuration

- allow users to specify a hostname, custom env variables…

I hope you learned something along the way !